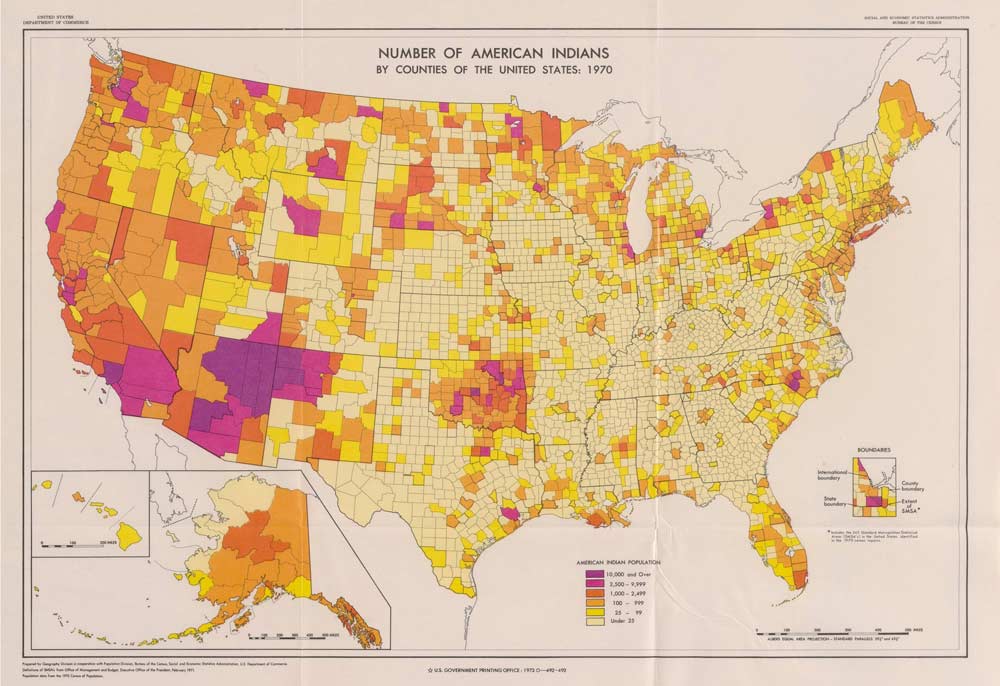

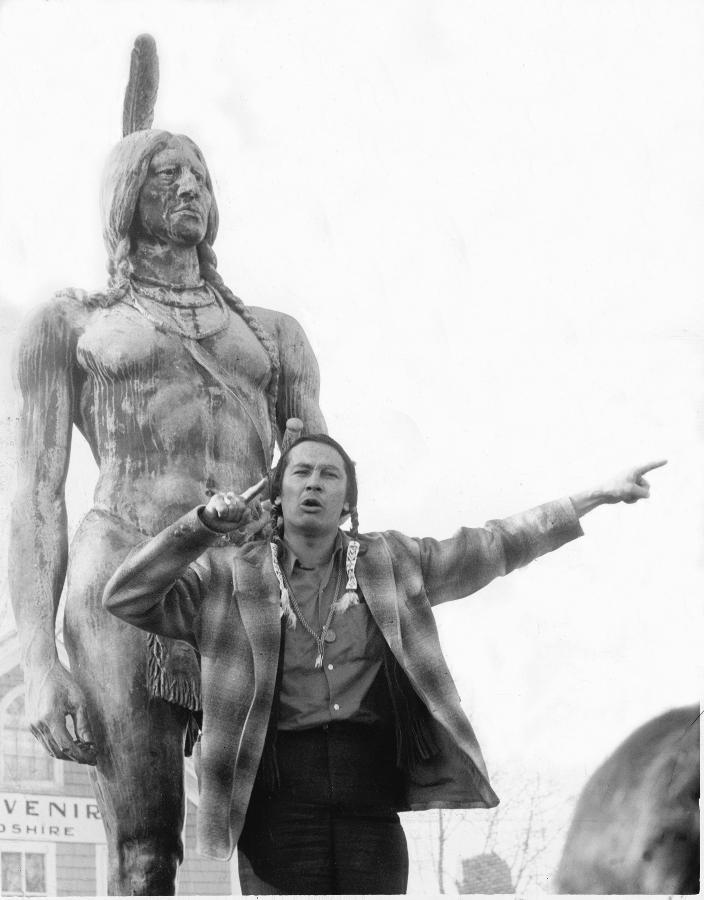

To highlight the loss of indigenous culture and the decimation of Native populations since the arrival of the Europeans in North America, AIM members organized a Thanksgiving Day protest in Plymouth, Massachusetts on the 350th anniversary of the Pilgrims’ arrival.

Protesters gathered at the statue of Massasoit, an important Wampanoag Indian leader in 1620. American Indian Movement leaders Russell Means and Dennis Banks delivered speeches condemning the romanticized portrayal of Thanksgiving as ignorant and inaccurate. Protesters also climbed on the replica of the Mayflower demanding that Thanksgiving should be considered a National Day of Mourning and not a celebration of colonialism.

AIM’s Thanksgiving Day protest, taking place during the Occupation of Alcatraz in California, increased national awareness of AIM and defined AIM’s advocacy as strident and vocal. Importantly, the 1970 protest at Plymouth Rock initiated a nationwide conversation about the inclusion of Native perspectives in American history that is still ongoing.

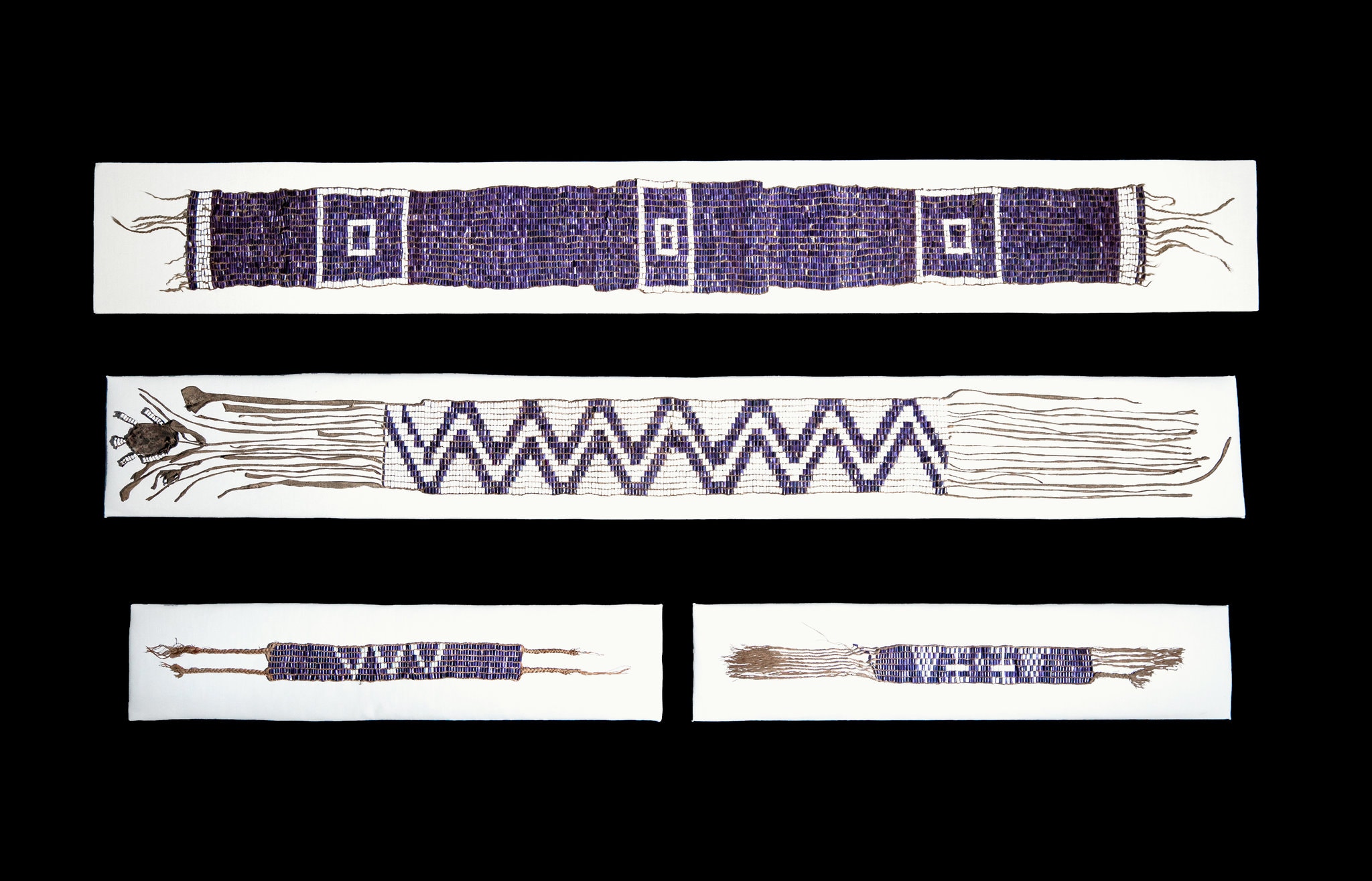

In 2020, for the 400th anniversary of the Pilgrim’s arrival, the annual celebration of Thanksgiving at Plymouth, Massachusetts will offer both historical and contemporary perspectives on the original historical event by including voices from indigenous, English colonial and American communities. Newly created wampum peace belts by Wampanoag artists will tour England as part of an exhibition featuring Native history. Fifty years later, the legacy of AIM’s Thanksgiving Day protest will be evident on both sides of the Atlantic.

Faces of AIM

Anna Mae Aquash

"I am Indian all the way and always will be. I’m not going to stop fighting until I die, and I hope I’m a good example of a human being and of my tribe."

Anna Mae Aquash

March 27, 1945 – late November

1975 (actual date of death unknown)

Tribal affiliation: Member of the Indian Brook First

Nation, Nova Scotia, Canada

As an Indian child of the relocation era, Anna Mae Aquash grew up in poverty on the Mi’kmaq reservation. At age 17, with only an elementary school education, Anna Mae moved around New England, working as a migrant farmhand until marrying and moving to Boston. Raising her two daughters, Denise and Deborah, in the United States, Anna Mae struggled with urban poverty and racism. With an increasing interest in advocacy for the preservation of tribal traditions and the extension of Native rights, she founded the Boston Indian Council, which introduced her to the greater fight for Native liberation and agency.

In 1970, she then joined AIM and became increasingly active, participating in the anti-Thanksgiving National Day of Mourning in Plymouth, Massachusetts that same year. She was also among the crowd of AIM protesters during the Trail of Broken Treaties, the occupation of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and the demonstration at Wounded Knee, South Dakota. In sustained conflict with the federal government at this time, AIM was the target of destabilization tactics, as rumors flew about internal spying and Native FBI informants. Arrested and charged for possession of weapons and for aiding Indian fugitives, Anna Mae was released on bail in November 1975 from the courthouse in Pierre, South Dakota, after which she presumably disappeared, not to be found again until her body was discovered in a ravine on the Pine Ridge Reservation in February 1976. For a while, she was believed to have died from exposure, but it wasn’t until February 2004 when Arlo Looking Cloud and John Graham, two former members of AIM, were tried, convicted, and sentenced to life for Anna Mae’s murder.

Anna Mae Aquash, murdered with the unfounded assumption that she acted as an FBI informant, was victimized by the increasing paranoia, suspicion, and violence that festered within the American Indian Movement. Furthermore, the deferment of justice for Anna Mae’s case and the building of hostility towards her as an influential member paints a disappointing image of how women were sidelined and scapegoated within the American Indian Movement.