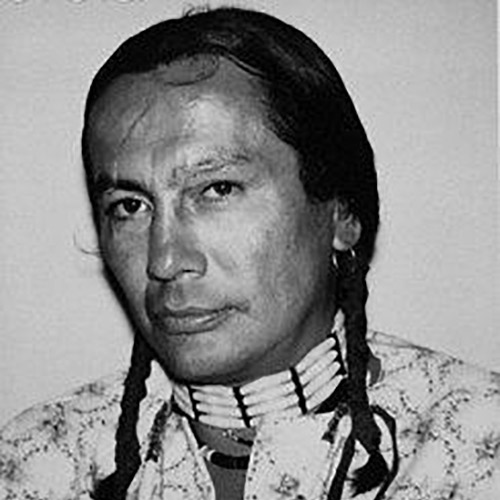

Russell Means

Russell Means

November 10, 1939 – October 22, 2012 | Tribal Affiliation: Oglala Sioux | Other names: Wanbli Ohitika (Brave Eagle)

This photograph was used in by Andy Warhol for his silkscreen, The American Indian (Russell Means), 1976.

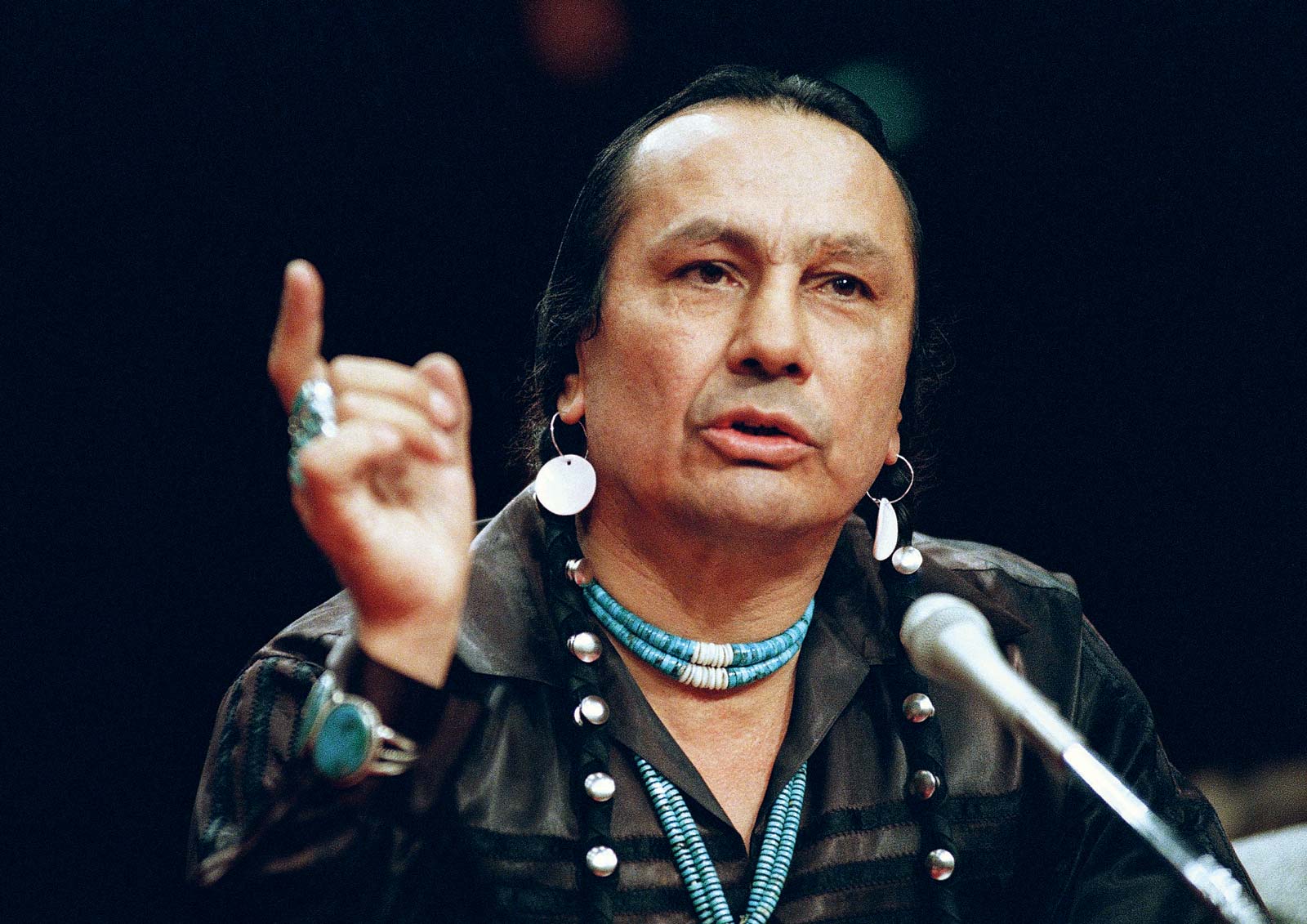

"Before AIM, Indians were dispirited, defeated, and culturally dissolving. People were ashamed to be Indian. You didn't see the young people wearing braids or chokers or ribbon shirts in those days. Hell, I didn't wear 'em. People didn't Sun Dance, they didn't Sweat, they were losing their languages. Then there was that spark at Alcatraz, and we took off. Man, we took a ride across this country. We put Indians and Indian rights smack dab in the middle of the public consciousness for the first time since the so-called Indian wars."

Means, an Oglala Sioux, was born on the reservation at Pine Ridge in 1939. He was a major figure in the American Indian Movement. On Thanksgiving Day in 1970, Means spearheaded an AIM protest on the Mayflower Replica in Plymouth, Massachusetts. This action drew nation-wide attention to the issues of colonization experienced by indigenous people.

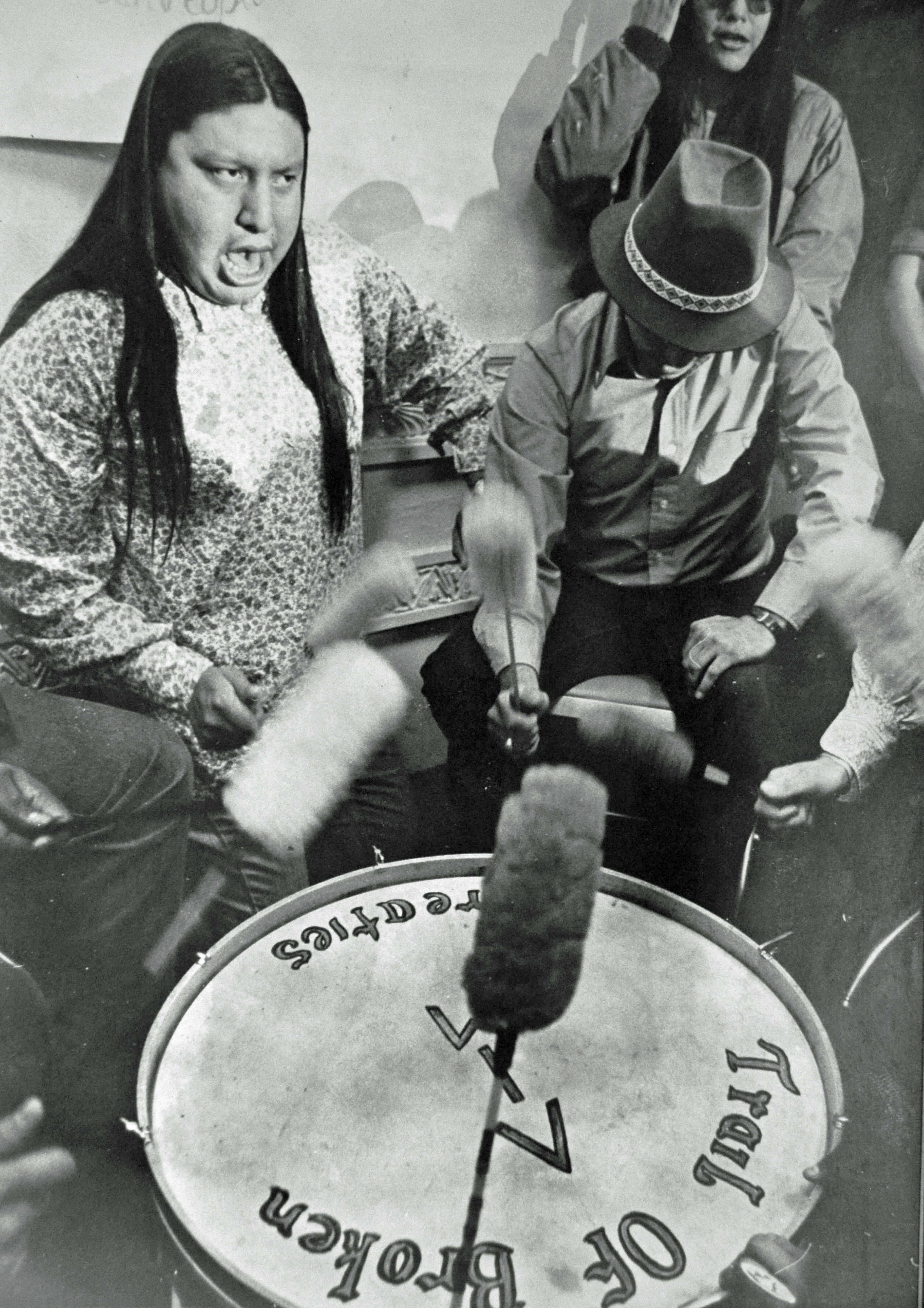

In another act of defiance, Means held an AIM prayer vigil held on Mount Rushmore to protest against the designation of the site as a national park. Means and his AIM members and supporters declared the national park was in violation of the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie which recognized the Sioux’s historical claims to the Black Hills. In 1972, Means also led people, AIM members and a coalition of tribal supporters, to Washington D.C. in the Trail of Broken Treaties caravan. However, while in D.C. government officials refused to meet with the protesters. In response, the protesters raided the Bureau of Indian Affairs, claiming the action was in protest to the U.S. Government’s numerous broken treaties over the centuries.

With the U.S. government’s eventual response and support for a policy of self-determination for Native people, AIM’s activism was replaced by pan-tribal and tribal actions in support of sovereignty. In his later years, Russell Means found work in Hollywood, appearing in over 30 films including the “Last of the Mohicans” and “Natural Born Killers.” Means was a charismatic figure who succeeded in garnering the attention of the press and he worked throughout his life to promote activism on behalf of Native communities. Means died in 2012 on the Pine Ridge Reservation; he will be remembered as an activist, politician, writer and major figure in the AIM Movement.

Leonard Crow Dog

Leonard Crow Dog

August 18, 1942 – present | Tribal Affiliation: Sicangu Lakota

Belonging to a lineage of influential medicine men, Crow Dog accepted Dennis Banks’ request to serve as the spiritual leader of AIM in 1970. A supporter of pan-Indianism and revitalization of traditional Native practices, Crow Dog was responsible for extending AIM’s goals beyond equitable justice and tribal sovereignty. He was an active participant in 1972 protests across South Dakota against the exonerated murder of Natives by white Americans. Leaders of AIM also sought his counsel during the 1972 takeover of the BIA and Wounded Knee II in 1973. In such escalated conflicts, Crow Dog treated wounded AIM members with traditional forms of Native medicine. Crow Dog’s family home on the Rosebud reservation, Crow Dog’s Paradise, acted as an AIM settlement, hosting Native and non-Native allies from across the country throughout the 1970s.

In 1975, Crow Dog was sentenced to 21 years in prison. The charges stemmed from two misrepresented assaults at Crow Dog’s Paradise and his abetting actions at Wounded Knee II. Crowdog’s sentence was reduced to two years following public outcry. Crow Dog currently serves as medicine man to the Sicangu Lakota Oyate Sioux of the Rosebud reservation in South Dakota. An author and musical artist, he continues efforts of Lakota cultural revitalization.

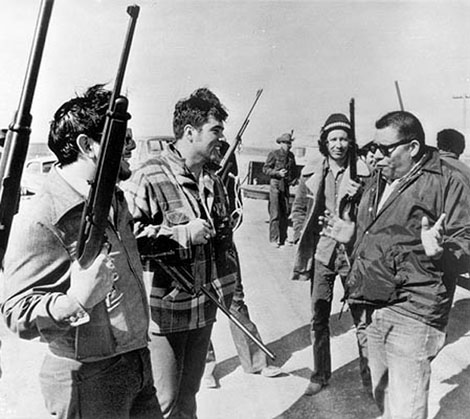

Richard A. Wilson

Richard A. (Dick) Wilson

April 29, 1934 – January 31, 1990 | Tribal Affiliation: Oglala Lakota Sioux

"What is happening at Wounded Knee is all part of a long-range plan of the Communist party...to combat this we are organizing an all-out volunteer army of patriots...They want to be martyrs? We will make it another Little Bighorn."

Perhaps the most prolific antagonist to AIM’s efforts of cultural revitalization and systemic reform, Dick Wilson served as tribal chairman of the Oglala Lakota Sioux of Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota from 1972-1976. Accused of being corrupt and dictatorial, Wilson appeared to act in favor of his family members and other mixed-race, assimilated Lakota people while ignoring the concerns of more traditional residents. His infamous Guardians of the Oglala Nation (GOONs), a federally funded private police force, terrorized Pine Ridge Reservation residents who spoke against his regime. After failed efforts to impeach and remove Wilson from office on grounds of nepotism, approximately 200 AIM members came to aid Oglala Lakota leaders in an attempt to forcibly revoke Wilson’s power. From February 27 until May 8, 1973, AIM members and federal agents engaged in the violent armed conflict known as the Occupation of Wounded Knee.

AIM members claimed that Wilson’s re-election as tribal chairman in 1974 was rigged. Having the highest per capita murder rate in the country from 1973-1975, Pine Ridge Reservation sufferred under Wilson’s control. Modest estimates indicate Wilson’s GOONs to have been responsible for over 100 reservation murders. Unsurprisingly, Wilson lost his 1975 bid for reelection and moved off the reservation. Returning to Pine Ridge years later, he was campaigning for a tribal council seat at the time of his death.

At Means' death in 2012