Third Space of Sovereignty

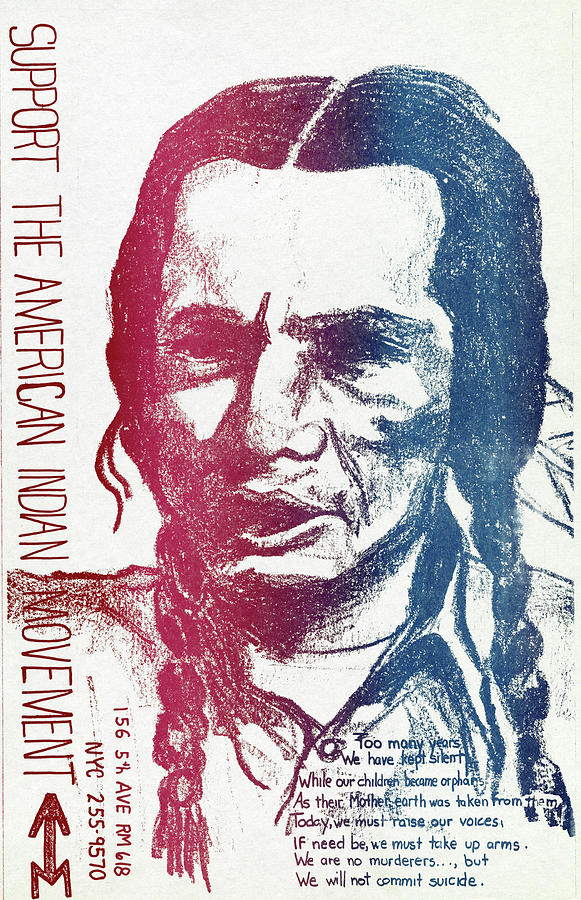

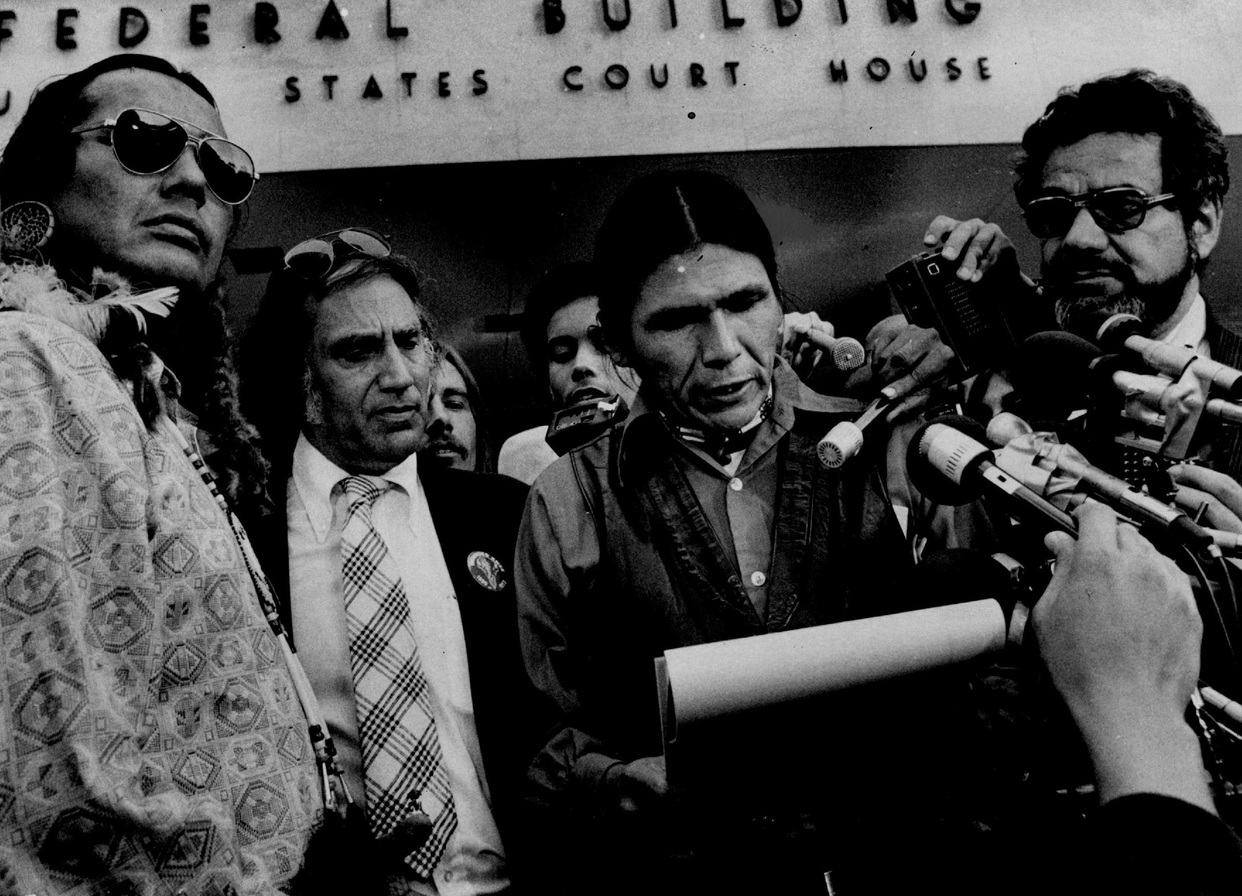

The American Indian Movement was the most visible activist group of the Red Power movement of the late 1960s and into the 1970s. The charismatic leaders of AIM promoted direct-action protests to draw attention to the problems in Indian country, particularly the numerous treaty violations for which they sought restitution.

AIM’s initial focus was centered on the problems faced by urban Indians, as a result of the federal government’s Termination Policy. Influenced by some of the Native American intellectuals of the day, AIM argued loudly for tribal self- determination and advocated for the restitution of treaty rights. The treaty process was predicated upon a recognition of the inherent sovereignty of indigenous people, based on their occupation of North America prior to colonialization and the founding of the United States.

Supreme Court decisions, most notably those of Chief Justice John Marshall in 1823 (Johnson v. M’Intosh), 1831 (Cherokee Nation v. Georgia) and 1832 (Worcester v. Georgia) defined the basic framework of federal Indian law in the United States. By designating Indian tribes as domestic dependent nations, the Marshall court rulings underscored the unique political status of tribes as distinct from both federal and state government. This third space of sovereignty, confirmed in treaties, legislation, the U.S. Constitution and multiple court cases, nevertheless remains a contested space.

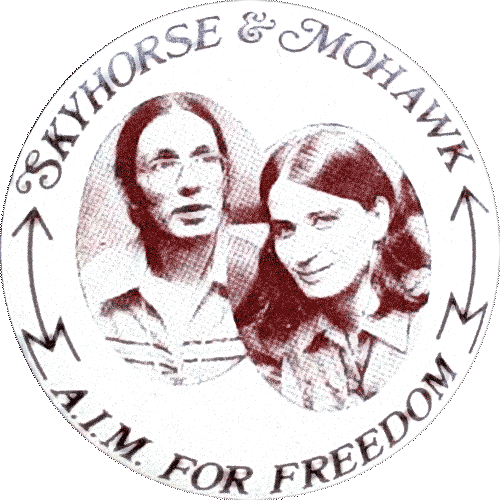

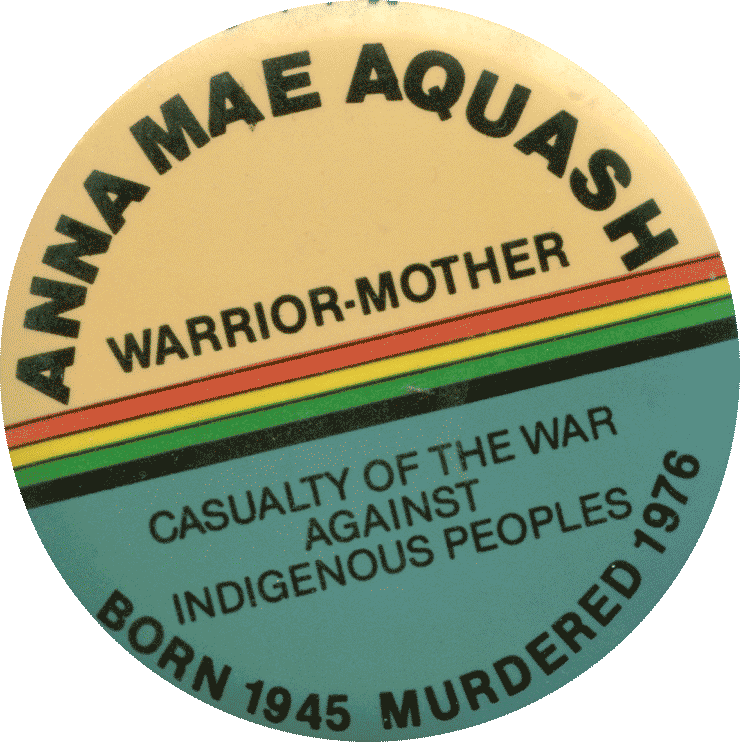

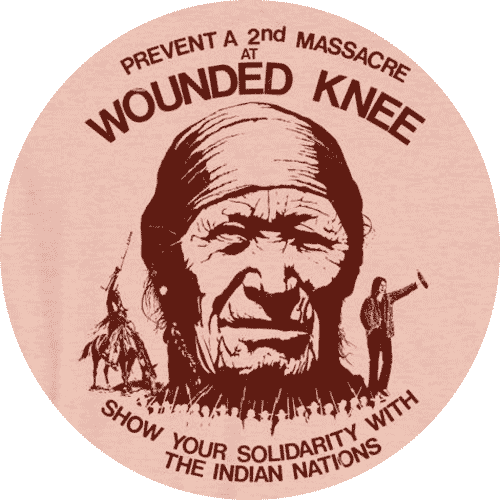

After the surrender of the protestors at the siege at Wounded Knee II in 1973, AIM leaders were arrested and constrained in lengthy court cases which thwarted the organization’s activist agenda. Later, internal factionalism among AIM leaders further undermined the organization. In 1993 AIM split into two groups, the AIM Grand Governing Council, headquartered in Minneapolis, and the International Confederation of Autonomous Chapters, headquartered in Denver.

.jpg)

More than 50 years after the rise of AIM, the organization’s impact can be seen in the legislation it inspired, such as the Indian Self-Determination and Education Act (P.L. 93-639) and the American Indian Religious Freedom Act (P.L. 95-341). Moreover, the resurgence of Native American communities is visible in the 573 federal status tribes seeking to reclaim their cultural heritage and rightful place in history. The struggle to retain control of the third space of sovereignty is ongoing to the present day.

Menominee Restoration Act in 1973 Administration for Native Americans (ANA) / Indian Health Service / Health Care Improvement Act (P. L. 94-437) / Indian Education Act / Indian Self-Determination and Education Act of 1975 (P. L. 93-638), American Indian Religious Freedom Act (AIRFA), P. L. 95-341, Bureau of Acknowledgement and Research (BAR), Tribally Controlled Community College Act (TCCA), Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) (P. L. 95-608)

Photos from the Dakota Access Pipeline Protests, April 2016 - February 2017

Members of the Standing Rock Sioux tribe with supporters from other tribes and environmentalists, opposing the construction of the energy pipeline, claiming it violated treaty rights and would harm the Missouri River, an important source of water for the reservation.

“It's not revolution we're after; it's liberation. We want to be free of a value system that's being imposed upon us...”

- John Trudell

(We Are Power, July 18, 1980: Intercultural Survival Gathering)

AISA Student Leaders with President Katherine Rowe

AISA Student Leaders with President Katherine Rowe