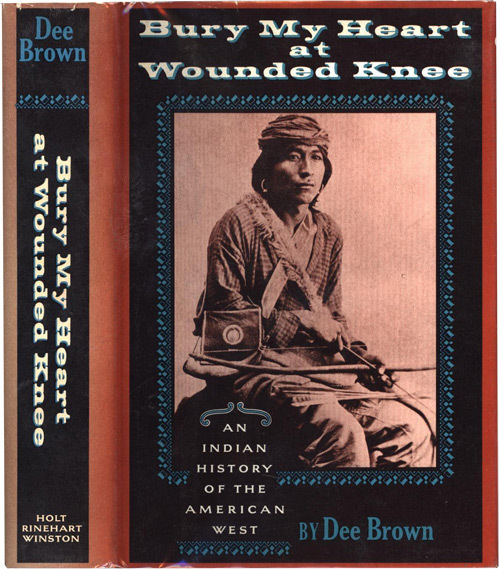

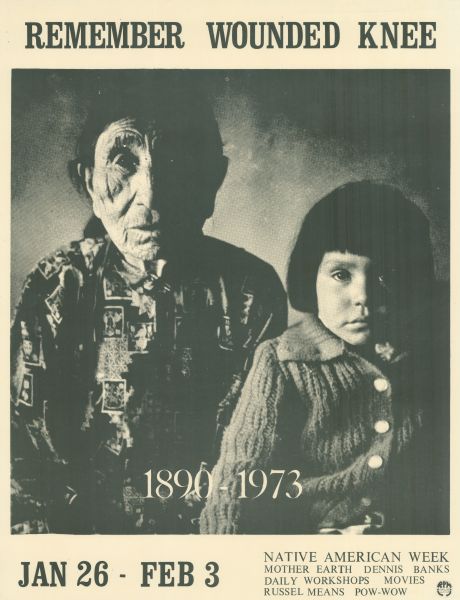

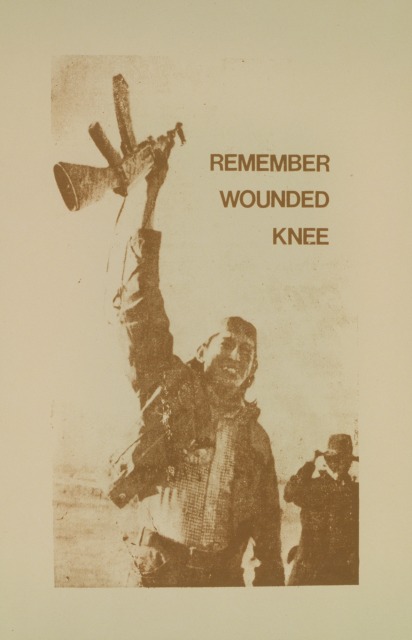

The protest sought to dismantle an allegedly corrupt tribal government but was also a strategic bid for national attention. The 1970 national best-seller Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee by Dee Brown presented Native American history in harsh relief. Brown’s historical overview of the American government’s military actions and broken promises to Indian tribes sensitized the general public to the issues being raised by the Red Power movement. The title of the book was a reference to the 1890 massacre of Lakota people at Wounded Knee, South Dakota. With the heart-wrenching details of the 1890 Wounded Knee event in the thoughts of many Americans, AIM members gambled that making another stand at Wounded Knee would get them the attention of a sympathetic national audience.

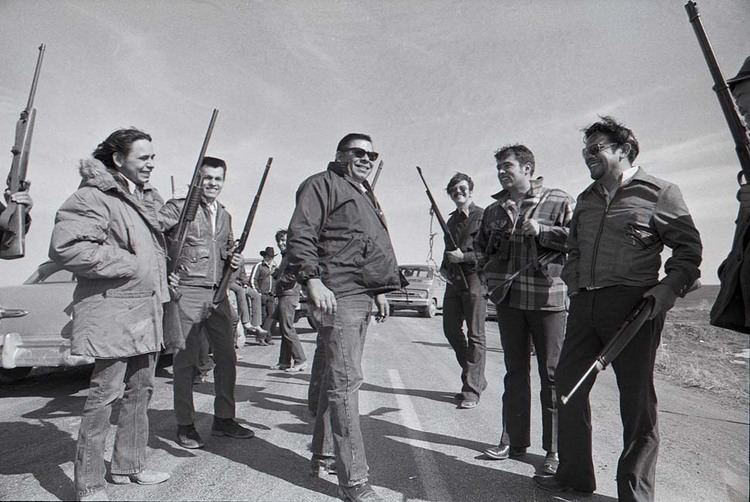

Under the leadership of tribal chairman Dick Wilson, the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation was deeply factionalized between progressives, whose interests aligned with Wilson and the federal government, versus traditionalists, who accused the tribal government of mishandling tribal funds and establishing a dictatorial, self-serving regime. Amid this factionalism, Wilson created a private police force, popularly known as the “Goon Squad.” This force was accused of carrying out ruthless violence against the traditionalists. AIM entered into this factionalized environment, escalating the tensions at Pine Ridge.

“...when the federal government has yielded, conceded, and appeased, we will march into Wounded Knee and kill tokas, wasichus, hasapas, and spiolas. They want to be martyrs? We will make it another Little Bighorn.”

- Dick Wilson, (Crow Dog 1996:204)

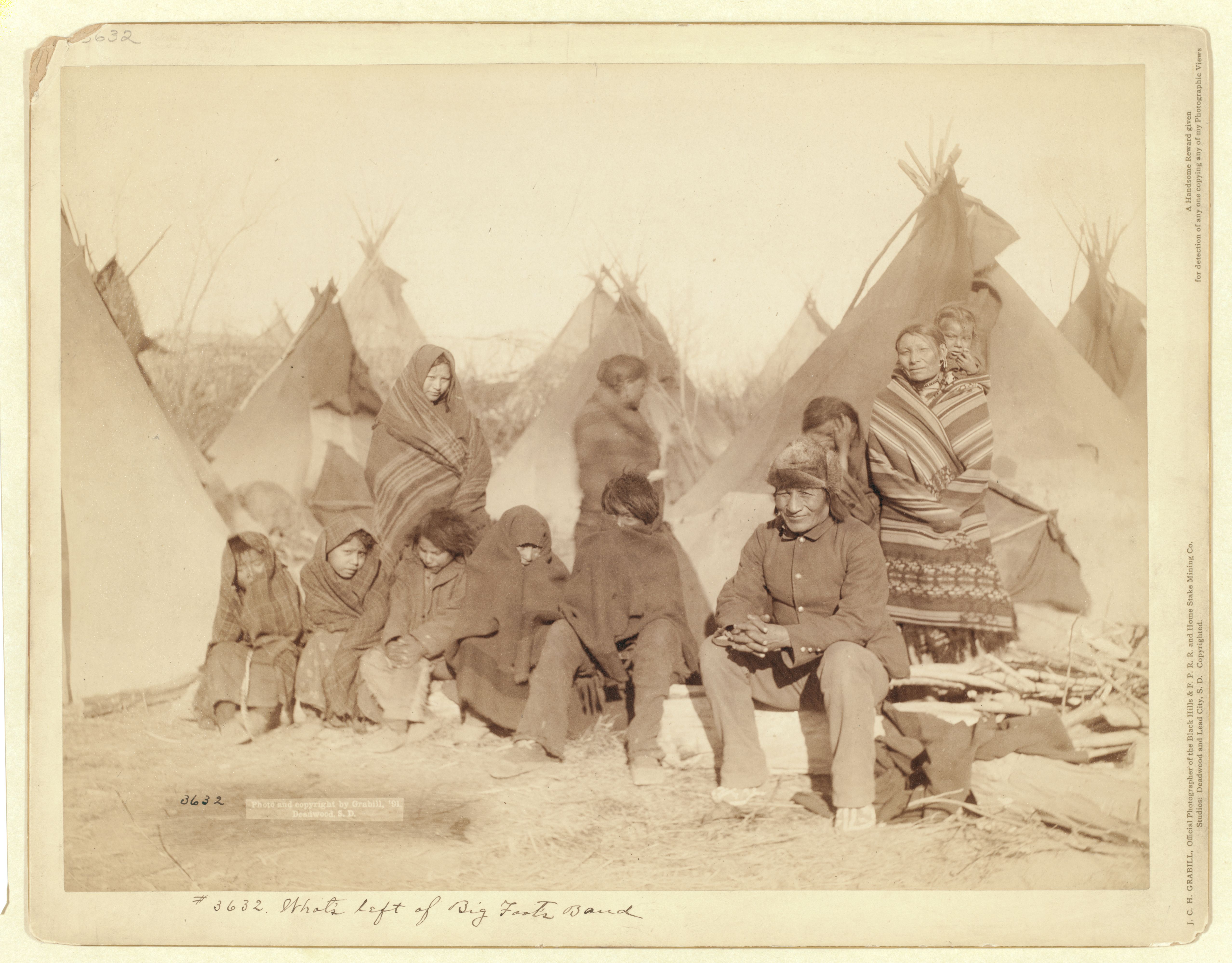

The murder of two Native men from the Pine Ridge Reservation and the lack of police action to solve the off-reservation murders mobilized Red Power activists and precipitated AIM’s occupation at Wounded Knee II. In 1972, AIM led a protest seeking justice for murdered Pine Ridge native Raymond Yellow Thunder. In January of 1973, one month before Wounded Knee II, AIM organized protests in Hot Springs, SD over the murder of Wesley Bad Heart Bull. In both protests, AIM members clashed with the local police and AIM’s charges of police brutality were downplayed by Wilson’s tribal government. Moreover, Wilson declared that AIM members and their supporters were troublemakers and would be “dealt with” by the tribal government. Responding to a request from Oglala Sioux traditionalists to remove Dick Wilson as tribal chairman, a contingent of AIM members arrived at the site of the 1890 Wounded Knee massacre on February 27th to make a stand.

.jpg)

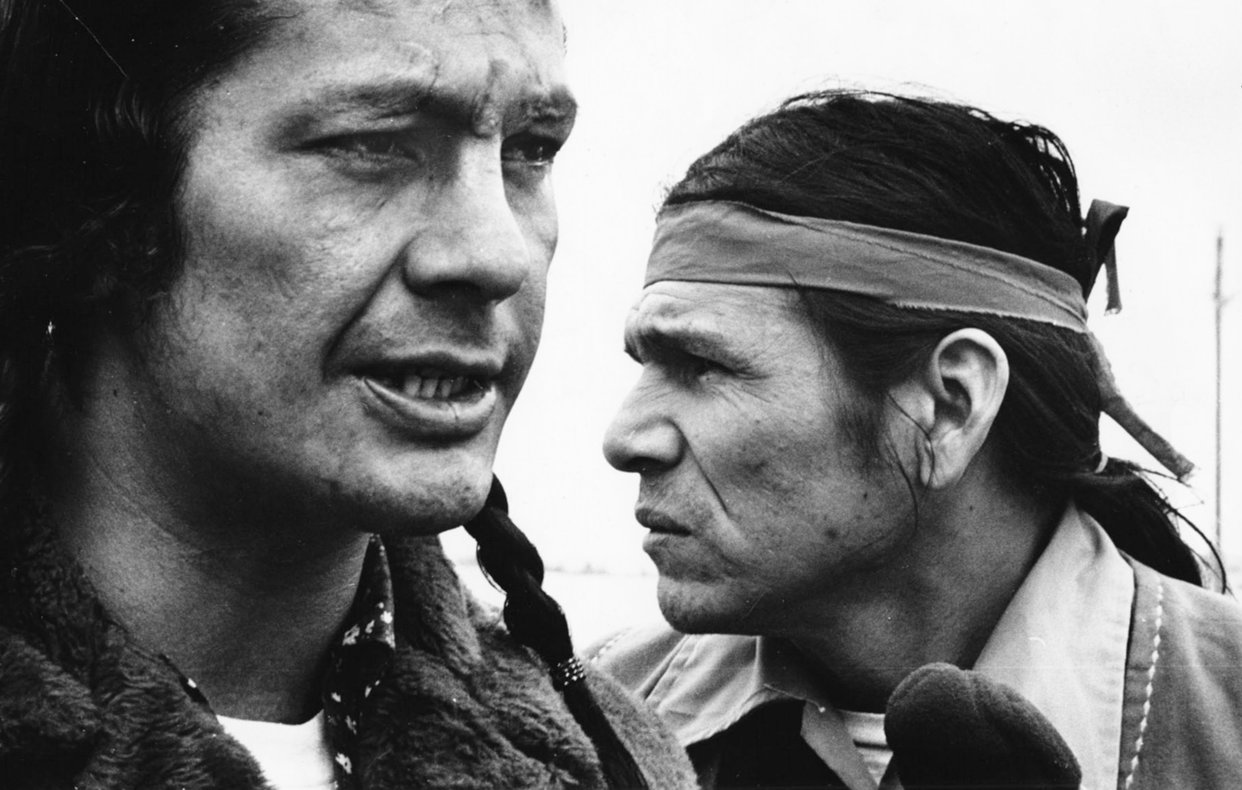

As the AIM occupiers dug in – forming a perimeter of nine closely guarded bunkers – they were surrounded by armed tribal and federal forces who implemented roadblocks. Both sides began exchanging the gunfire that would continue throughout much of the occupation. AIM leaders Russel Means and Dennis Banks adeptly used media coverage to gain national attention for their cause and sparked protests elsewhere in support of the occupation. The 71-day siege continued against a background of demands and counter demands, stalled negotiations and the eventual breakdown of a peaceful agreement.

“This is not an AIM action, it’s an all-Indian action. They can’t do anything worse than kill us. The feds will be coming soon. Be prepared to defend this position with your life! What is at stake here at Wounded Knee is not just the lives of a few hundred Indian people, but our whole way of Indian life.”

- Dennis Banks

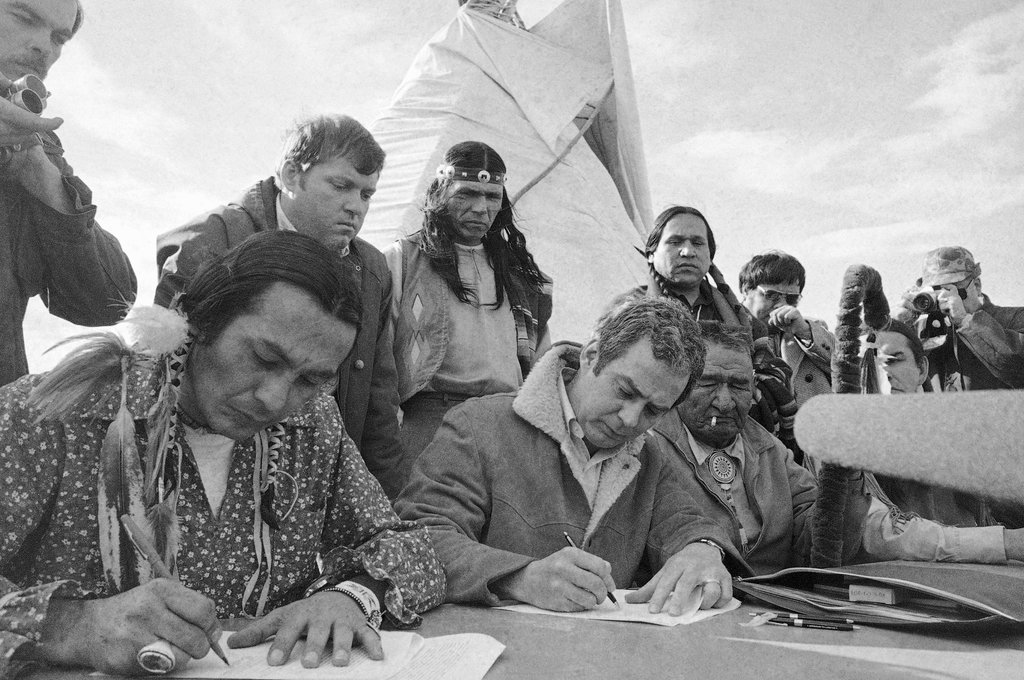

On March 11th, federal and tribal forces lifted the surrounding roadblocks to Wounded Knee allowing both additional supporters and supplies to enter the site. In a press conference, citing the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie, occupiers declared their territory the Independent Oglala Nation and requested a meeting with the U.S. Secretary of State. This meeting was never held and, on April 5th, after continued firefights, AIM leaders reached an initial agreement with the opposition leaders from the federal and tribal governments. This agreement stated that an AIM delegation would be permitted to travel to Washington, D.C. to express their grievances and that the federal government would open an investigation into Wilson’s criminal activity. The discussions failed; the occupation continued. Supporters sympathetic to AIM organized airdrops of food and supplies as the federal government attempted to starve the occupiers into submission. Morale waned with the deaths of two Natives, Frank Clearwater and Lawrence “Buddy” Lamont. With dwindling support for the resistance, the occupiers finally reached an agreement to stand down on May 8th, 1973, albeit with promises from the White House to investigate their complaints.

Following the occupation, the federal government indicted hundreds of AIM members for their involvement, including AIM leaders. Most charges were for petty crimes. Few were convicted, but the government did succeed in paralyzing the movement by tying its members up in court. Though the occupation led to few concrete changes in conditions at Pine Ridge, today it remains a rallying cry for continued resistance to federal mis-governance and a symbol of Native American pride.

“To us, self-determination means a return to our status as a sovereign race, a sovereign people in the United States."

- Wes Studi (Cherokee AIM Member)